British academics don’t want to be excluded

In her speech at the convention of her conservative party, Theresa-Dancing-Queen-May stated that freedom of movement of people, the way it works in the EU now, will end with Brexit. Amongst members of her own party, this statement was met with support, but for many students from the UK, the consequences are decidedly less positive. May states EU citizens won’t be able to enter the UK as easily anymore. Curently, it’s easy for students within the EU to study abroad or go on exchange in a different EU country, thanks to the freedom of movement. It seems plausible that, in response to May’s statement, the EU will mirror her position – which means that starting January 2020, European students won’t be able to enter the UK for studies as easily anymore, and students from the UK will have the same issues when going on exchange to an EU country.

No more cheap Master’s

Will it actually happen? The answer can’t be predicted yet. Will the current regulations – for instance the Erasmus programme and other grants that are linked to it – continue to exist? To the best of my knowledge, the answer is yes.

It’s expected the UK will continue to participate in the programme, and will keep paying its dues for it. The British government understands that it’s an important experience for British students, and they won’t be stupid enough to obstruct something that’s got so much symbolic value, and yet doesn’t cost much.

Another thing is when it comes to doing an entire study programme in the EU, as a few of my Master’s students have done. They came to Utrecht for their education, partially because the tuition here is much lower than what they’d pay in their home country: 2,060 euros versus 9,250 pounds in the UK (at the current exchange rate, that’s approximately 11,000 euros). Quite the difference, indeed. And it’s popular because, as my students tell me, the Netherlands is a great country to live in, as it’s relaxed, open, friendly, most people speak excellent (European) English, the quality of the classes is high, and it’s close to home as well as cheap. A good reason to study here.

These Master’s students employ an EU regulation that stipulates students from the EER (European Economic Region) – that’s the EU countries plus Switzerland, Norway and Iceland – have to accept each other’s students at the cost of the regular tuition.

Teachers’ exchange

It’s improbable that this deal will continue to exist post-Brexit. The UK will become, in EU jargon, a third country, no longer a member of the EER. The question is whether we’ll see a sharp increase in the number of UK students who still want to profit from the current regulations. The UU numbers show an increase in British students in 2016, but the trend didn’t continue in the years after.

Within the borders of the EU, there’s also the opportunity for teachers to visit programmes in other EU countries. Will this programme abolished as well? I don’t think so. These programmes, as far as they’re within the bounds of the Erasmus programme, are mobile. The exchanges with the UK will probably see an increase in paperwork. The same is expected of the sabbatical visits to UK universities/research labs. The receiving universities, especially, will have a lot more paperwork to work through.

PhD tracks

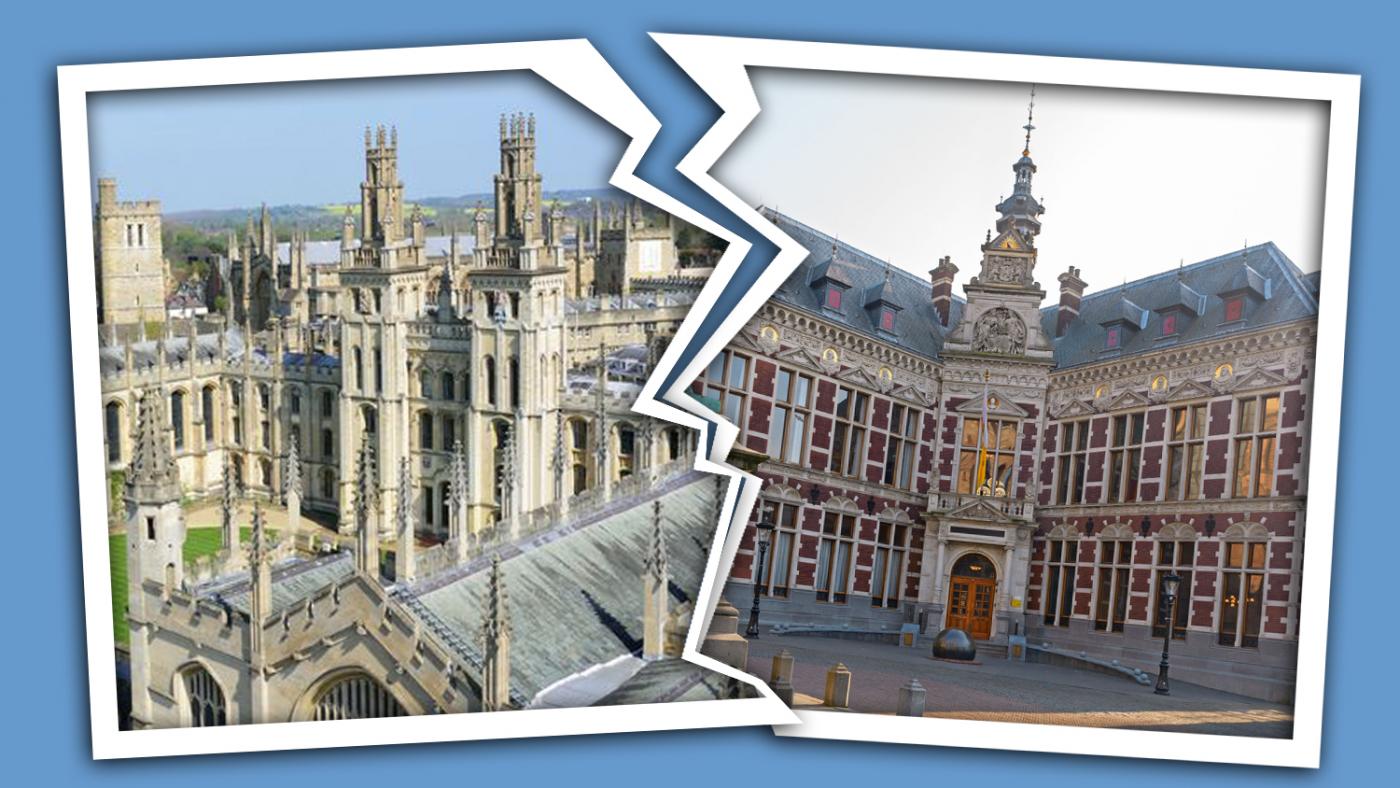

One of my Master’s students, graduated cum laude, continued his education at a Master’s programme in Oxford, followed by a PhD programme. Studying at a hors catégorie university such as Oxford may be expensive, but the 11,000 euros a year are doable with help from (grand)parents and other members of one’s family, and give your resume a boost that pays off in time. If you can follow up with a paid PhD scholarship, a career in science is all but secured.

Does it pay off for Bachelor’s students to go to the UK? A prerequisite is for EU students to be admitted to the UK’s top universities. That in itself isn’t impossible, as the Dutch vwo diploma is the equivalent of the international Baccalaureate, and has prestige mostly when combined with excellent grades (an average of 7.5 or higher). The problem of the programme’s costs remain.

Decrease in immigration

For both the prospective Bachelor’s student and the PhD candidate, an additional problem arises. Brexit can not be seen separately from the demand for a decrease in the influx of immigrants. In her position as minister of Internal Affairs, Theresa May has repeated time and again that immigration into the UK has to go down from its long-term average of 300,000 to around 25,000. That 300,000 number includes the influx of students. Since the Brexit referendum, a slight decrease in the numbers has already been observed. If the influx of migrants has to go down to a tenth of its long-term average, a reduction in the influx of students is an inescapable conclusion. The current minister of Internal Affairs, Sajid Javid, has shown signs of having a different point of view on this issue.

He’s currently studying whether it’s possible to exclude the students who come to the UK from the immigrant totals, as they’ll leave in time anyway. Students’ situations are more circular migration rather than permanent settlement. The Dutch figures: after two years, 35 percent have left, and after ten years, practically everyone has left the country. In Javid’s considerations, an important factor will be the fact that the UK’s educational system depends, for a large part, on tuition fees paid by external students. Because PhD candidates in the Dutch students have employee status, the figures of students who come to our country and continue their education as TA are completely different. There are currently no migration limitations to be expected there.

Permanent work

It’s harder to estimate what happens when someone wants to permanently work at a knowledge institution or university in the UK. A minimum salary is being mentioned of 30,000 pounds (around 36,000 euros), required for obtaining a work permit. For scientists, of course, that won’t be a problem. But it’s unclear whether there’ll be other requirements for employees. Nor is it clear whether pensions built up in the UK can be taken back when and if that person ever decides to return. And there are some other issues to be discussed in the area of social security, where it remains entirely unclear what the situation will be.

One thing that is clear is that the researchers who are currently in the UK but don’t have the British nationality are anything but optimistic. A study conducted among foreign researchers who work at the prestigious Francis Crick Institute, the biggest biomedical institute in Europe, shows that 40 percent is considering to leave when the UK leaves the EU. In the case of hard Brexit, almost everyone is convinced it’ll be disadvantageous to the institute because there are so many researchers there with an EU background, and staying at the Crick will be difficult and expensive.

ERC grants

There’s also a fear of the consequences of the possible end of the many ERC grants. In early September, I was in London for a convention. The hullabaloo about Brexit was quite something, and especially somber. Especially because people are worried about the ERC funds. The British government has stated that generally, all net income British people gain from EU subsidies etcetera, which will be cancelled due to Brexit, will be compensated. This is the so-called Brexit divident, which can be created because the UK no longer has to pay its membership contribution to the EU and the UK is a net contributer. Whether that exists remains to be discussed, but will for the purposes of this writing be ignored. It is clear, however, that the UK currently contributes 2 billion euros to the ERC fund, and receives 3.2 billion from it. At the UK universities, no one thinks the British government will actually pay the difference. Especially not in the Humanities.

Should the UK continue its participation in the ERC system? Switzerland, as EER country, also participates in the fund, so it’s not impossible. May’s Chequers plan says, in a nutshell, that the UK wants to stick with the system. The question is whether the EU will agree to this. The Europen commission has already announced that continuation applications for ERC grants will be problematic if they include English partners and the period ends later than the March 29, 2019 Brexit date. That was the other reason that caused the slightly offensive mood in London concerning Brexit. British academics can already feel themselves being excluded, and are incredibly unhappy about it.