Dutch students and international students: two worlds apart?

“Internationalisation features high on the agenda of Utrecht University”, stated Rector Henk Kummeling in 2019. In its new Strategic Plan, UU states that everybody should feel welcome and at home at the university. We can therefore assume that the number of international students will keep on growing. Currently, six of UU’s 50 Bachelor’s degrees are taught exclusively in English, with an additional seven programmes offering students the possibility to follow it fully in English. Of its more than 150 Master’s programmes, 103 are English-taught and 14 are multilingual. As a result, 3,251 of UU’s 30,000 students come from abroad.

“Almost all respondents agree there is a divide”, says Alexander Buse, one of the Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE) students behind the study, alongside Elzbieta Janusauskaite and Koen Willemen. They are Australian, Lithuanian, and Dutch, respectively. So far, they have surveyed 32 students across UU, of which 53 percent were Dutch and the remaining respondents, international (if you wish to take the survey too, you can do so here). Although the sample is not representative of the entire UU community, the preliminary results are telling and echo some of the findings of the most recent International Student Survey, which revealed that 76 percent of international students in the Netherlands would like more interaction with Dutch students.

In the PPE survey, over 73 percent of the international respondents and 82 percent of the Dutch respondents recognise a “social gap” between the two groups. Of those, 80 percent of internationals and 70 percent of locals perceive the gap as a problem. “Nearly 60 percent of Dutch respondents didn’t have any international friends, while 82 percent had barely any. In comparison, 80 percent of international students stated that nearly all their friends were international. It is, therefore, clear that a large segregation exists”, says Elzbieta. “Some of my friends think it’s weird that I’m friends with internationals”, says a Dutch respondent.

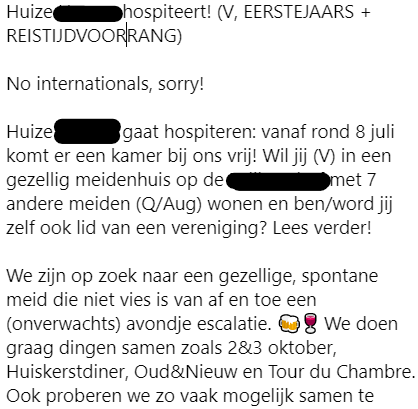

Screenshot of an ad posted on Facebook Marketplace, announcing a room in a student house and telling internationals not to apply.

Consequently, more than half of international respondents say they have felt excluded or discriminated against. Housing was mentioned as a big issue, as it’s not uncommon for student houses to write “no internationals” when looking for a roommate online. Once again, this result echoes the International Student Survey, in which 57 percent of those surveyed said they have had feelings of discrimination with regard to housing. Group work is another occasion when this can happen. “In one of my classes, during group project sign-ups, Dutch students would write ‘only Dutch students please’ above their group”, shares one of the respondents. In contrast, over 90 percent of Dutch respondents said “no” when asked whether they’ve ever felt excluded at UU.

Infographic made by PPE students Elzbieta, Alexander and Koen.

Language barrier

But what exactly is causing this rift? Language came first on the list of reasons, mentioned by 93 percent of internationals and 82 percent of locals in the PPE survey. “My level of English unfortunately isn’t high enough to make me feel comfortable talking to internationals”, explains a Dutch student. “Speaking the same language forms a bond”, says another. “Language differences make it harder to relate”, declares a third. An international respondent reasons that the Dutch tend to make jokes referencing their own language and culture, so the foreigner not catching them is less likely to become friends with the group.

Although the survey focuses on the social aspect, some international respondents feel as though their lack of knowledge of the Dutch language sometimes impairs them in class as well. One of the international respondents says: “People will start speaking Dutch even to professors in the tutorial, and professors also reply in Dutch about academic context (keeping in mind that it was an English-taught course)”. Another one complained that additional information or explanations to the questions are often given in Dutch, not English. On the locals’ side, not being “allowed” to use their mother tongue in class is sometimes felt as a nuisance. “It’s annoying when you have to follow a class in English because there are two internationals in a group of a hundred students”.

Reacting to these testimonies, Utrecht University said in a statement sent via e-mail to DUB: “We are a global education and research institute. This is why English has become a matter of course. Sometimes that means that you have to step outside your comfort zone. If a student in an international course indicates that they only want to work with Dutch people (because of the language barrier), they are depriving themselves and other students of an important learning experience. That’s not the way we would like to see things at UU. Excluding fellow students is, in any case, not acceptable. If something like that happens, it is important to raise the issue with the teacher and/or group”.

For many foreign students, realising that not speaking Dutch can come as a hindrance to their student lives is an unmet expectation. “When we apply to UU, we assume that English will be enough. Instead, what happens is that your integration is very limited if you don’t speak Dutch”, says Andreia Duque, one of the first two international students to be elected for the university council last academic year. She thinks the university isn’t transparent enough about this situation with prospective students.

“When students go to Spain, France, or South America, they know they have to learn the language”, says Michiel Dijkman, Member of the Management Board at Nuffic, the Dutch organisation for internationalisation in education. “But because the Netherlands is a small country of 17 million citizens, and the amount of people speaking English as a second language is high, one may assume there will be no language barrier”. However, “just because someone is able to speak a certain language, does not necessarily mean they want to do it at all times”, explains Jan ten Thije, Professor of Intercultural Communication.

In its e-mail to DUB, UU added: “Although English is becoming more common at UU, the university is at the same time anchored in Dutch society. A significant part of our students have Dutch as their mother tongue, and a part of the labour market for alumni is Dutch or bilingual. In addition, the university has a governmental duty of care to continue to stimulate Dutch as a language of higher education (as regulated by the draft bill Language & Accessibility, for instance)”.

Andreia Duque (left) beside Nandika Mogha. They were the first international members of the University Council. Photo: Ivar Pel

Andreia Duque (left) beside Nandika Mogha. They were the first international members of the University Council. Photo: Ivar Pel

Representation

The language barrier can also mean foreigners are having less of a voice regarding the university’s policies. As mentioned, UU’s council never had international members until 2020-2021, when the election of Duque and Nandika Mogha, who both spoke little Dutch at the time, led the university to consider whether the language of the council meetings should be changed to English, as is the case in the council of the Faculty of Science, for example. In the end, UU opted for luistertaal: an experiment in which Dutch council members would speak Dutch and international council members, English – with an interpreter to help out if needed and documents being issued in both languages. Mogha and Duque were provided with Dutch classes and all council members were offered two workshops on “Multilingual meetings” to improve their skills in dealing with multilingualism. In theory, this policy guarantees that everybody can speak the language they feel most comfortable with and the debate doesn’t lose its nuances.

In practice, however, there can be bumps in the road. Near the end of her term, Duque wrote an op-ed for DUB about her experience. “A one-year mandate is not enough to reach the proficiency in listening and reading in Dutch that is required to apply luistertaal”, she wrote, saying that the position demands a lot of “emotional endurance” from a foreign student. In a subsequent conversation with DUB, she added: “I feel like internationals are being accommodated rather than integrated”. She fears they will “simply give up” running for the council altogether. This year, there are no foreign students in the UU council, but some did get elected for the councils of their faculties.

Dylan van Tongeren, a Dutch student pursuing a Bachelor’s in Chemistry, is a member of the council of the Faculty of Science. He thinks the meetings work well in English because the overall level spoken by the members of the council is sufficient. “I can’t think of any instance in which English was a problem. In my experience, we can effectively represent students and staff in a second language. Everybody is able to switch back and forth from Dutch to English with ease, all the time, so having meetings in English is not an issue”. Like Andreia, he is in favour of a switch in the UU council. Asked about possible council members who don’t speak English that well, such as employees who are not highly educated, he replies that if UU wants to compete internationally, it is to be expected that the institution gradually makes English its lingua franca, “and the council is a crucial part of that as that’s how the university can improve”.

The research project Multilingualism and Participation (M&M in the Dutch acronym) was created to follow the council’s experiment and research other forms of multilingualism, aiming to map out the best solutions for participatory bodies. “Participating in these bodies contributes to making international students feel connected to the Dutch academic world. Not to mention they get to know Dutch students in the parties and council”, states Kimberly Naber, Intercultural Awareness trainer at UU, who’s involved in the research. She co-authored a reaction to Duque’s op-ed alongside Ten Thije, arguing UU must find a way to use both English and Dutch in the council.

“The fact that UU is a bilingual university naturally results in a number of organisational challenges. A language policy committee is examining these questions. The intention is to discuss a language policy plan with the University Council in the autumn”, informed Utrecht University. Additionally, UU has hired a Warm Welcome project manager, who will advocate for this subject, among other things. She will start working full-time in August.

Jan ten Thije. Photo: Didi van Zoeren, courtesy of the professor.

Other reasons

Language is not the only reason attributed to the perceived divide, though. Dutch students from other cities in the Netherlands often do not move to Utrecht, preferring to commute instead. “Their social life is elsewhere”, explains Ten Thije. “As for those born and raised in Utrecht, their social lives are pretty much settled as well. Many don’t feel a need to seek out international friendships”.

Another important factor is how long the international student will be here for. Naber: “It matters if they’re in Utrecht for a whole Bachelor’s or just a semester. Exchange students are often rejected by student houses not necessarily because they come from abroad, but because their stay is too short”.

Last but not least, let’s not forget international students can be averse to getting out of their comfort zone, too. After all, that’s only human. “For them too, it can be comfortable to stay in a bubble where everyone is having a similar experience”, says Naber. Because they’re willingly venturing abroad for their studies, one might assume internationals are very open-minded people. While that is true, open-mindedness also has gradations. “I feel like in some cases internationals do not feel accepted and also feel belittled by the Dutch and their fraternities, so an automatic response would be to dislike them”, writes an international student in the PPE survey.

“Yes, the divide exists and it’s a problem. But it’s not a specifically Dutch problem”, says Jan ten Thije, who has worked abroad himself. He spent six years teaching in Germany, also in an international environment. “Our neighbouring countries are tackling similar issues. Dutch students who go study abroad often have the same experience: they meet more internationals than locals”.

“Perhaps Utrecht University should be clearer in communicating that English is enough to follow the programme, but learning doesn’t happen only in the classroom. It also happens outside, in society, clubs, associations and the like, where most people speak Dutch”, notes Ten Thije.

That’s where student associations come in: they can play a pivotal role in getting the two groups together, says the professor. Student associations can apply for subsidy for certain activities, including initiatives related to their own internationalisation, such as translating their website to English. In addition, the associations able to demonstrate in their 2021 assessment that they have met at least two of UU’s “points of attention” are eligible for a larger share of the budget allocated to them. One of these points of attention is organising activities to involve international students in the institution. Next year, UU is planning to once again provide training for student organisations to engage more internationals.

What international students can do

So, what can students themselves do to tear down the wall? Dijkman advises international students to study Dutch before and during their studies, regardless of how long they’ll be staying. That way, they can acquire some basic knowledge that will come in handy not just at school, but also in daily interactions with shop clerks, service providers and the like. Additionally, try to learn as much about the culture as you can, as knowledge about the country’s history and society can help avoid unrealistic expectations and understand why the Dutch act the way they do.

UU offers the free online course Getting to know (the) Dutch to international students starting their studies the following semester. Similarly, ESN has a pre-departure mentor programme. In addition to the website Study in Holland, Dijkman recommends following Nuffic’s Instagram account, which is taken over weekly by foreign students sharing their experiences. Platforms aimed at expats, such as I am Expat, Expatica, and Dutch News can be useful, too. Once here, international students can join ESN’s Dutch courses and attend the Language Café. UU also partners with language school Babel to offer UUers a discount.

What Dutch students can do

As for Dutch students, seize the opportunity to speak English often and to engage with people from other countries without leaving your own, even if you don’t feel comfortable at first. After all, this experience is likely to be useful in a myriad of career paths, says Dijkman of Nuffic. “When you ask CEOs what kind of competences they need for their future employees, they always mention intercultural experience. In most companies, you’ll work together with people with different cultural backgrounds, but also other countries and languages. Even if you work for a small or medium-sized business that’s only based in the Netherlands, you will have to contact suppliers from Germany, France, China etc. The Netherlands also has a lot of tourists and expats, so it’s important for Dutch people to speak another language and understand that people from different cultural backgrounds act differently”, says Michiel of Nuffic, noting that “there are a lot of differences, but there are a lot of similarities too!”

He knows exactly how it feels to walk on eggshells while expressing himself in a second language. “When I started my studies, which were totally in English, it was not that easy. The level of English taught in high school is okay, but it’s not academic level. I think there should be both study programmes in Dutch and in English, but we shouldn’t forget that we are a small, trading nation”. Also in partnership with Babel, UU offers four online courses for Dutch students looking to brush up their English.

Other ideas

Study programmes and teachers can take matters into their own hands too. In the International Student Survey, respondents called for universities to ensure a diverse group composition during group assignments. That’s exactly what happened in the Master’s in Intercultural Communication. Jan ten Thije: “Students used to choose the group members themselves. Now we do it for them. We also established a buddy system, getting a local and a foreigner to work together”. It may come as a surprise that even students of Intercultural Communication need a little push. “They’re more enthusiastic than average, but it’s not automatic. It doesn’t go by itself. Therefore, the study programme must make sure there’s intense collaboration and hope that this bears fruit outside the classroom as well”, Ten Thije concludes.

Speaking of buddy systems, students in Utrecht can join BuddyGoDutch, a student organisation matching international students with Dutch students. Signing up is free. UU also has an academic buddy programme, aimed mainly at (prospective) exchange students.

As for the housing market, “when students write ‘no internationals’ in their ads, that’s pure discrimination. It happens mostly in the private market, where landlords choose who to rent to and student houses select roommates as they please. If the university wants to actively tackle this problem, then it must create more student rooms, with facilities that promote mingling”, suggests Ten Thije.

Dijkman recommends Dutch universities to share experiences with each other. “At Maastricht University, where I studied, everything was in English. Maybe UU is more Dutch-oriented? I think universities can learn from each other, too. We should find really practical solutions. How about having the first non-Dutch person in the UU Executive Board?”