A rocky start, and then came the crisis: minister van Engelshoven bids farewell

It was painful. On September 2, 2019, the then minister of education, Ingrid van Engelshoven, gave a speech at the gala opening of the academic year in Leiden, after being attacked in the newspapers that morning by her host, vice-chancellor Carel Stolker, of all people. “I’ve never known a time when relations were this bad – particularly given the favourable economic situation”, he wrote. Stolker promised to welcome the minister courteously but “we are not going to hide our opinion that her policy is simply disastrous.”

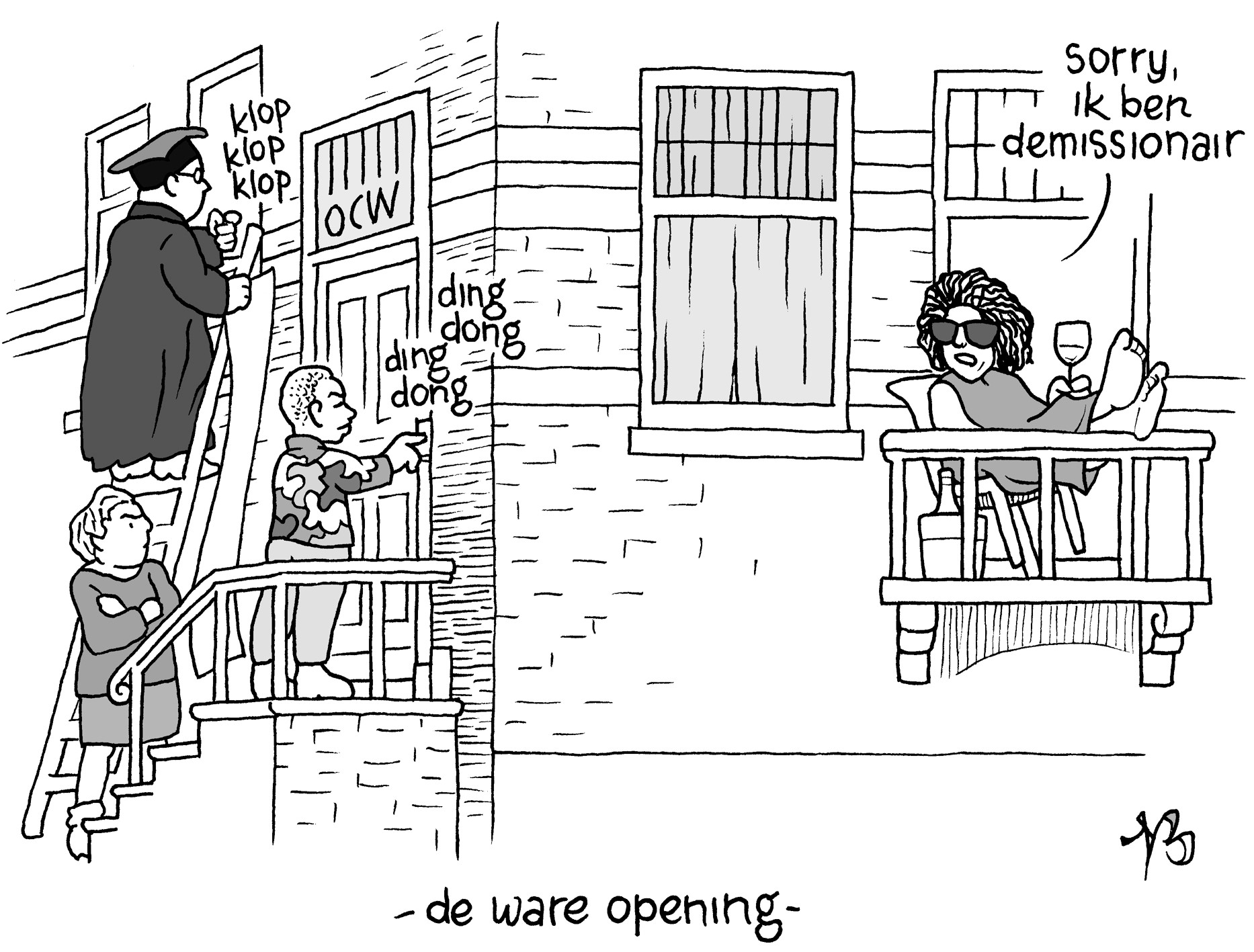

And Stolker was not the only one. Hundreds of activists gathered in Leiden for the "True Opening" of the academic year. Their leaders said they had lost confidence in the minister and called for her to resign. Could things get any worse than that?

DUB cartoonist Niels Bongers depicted the minister in his strips quite often. "Her voluminous hair makes her instantly recognizable and she has a very expressive face, although I usually made her look serious or worried for comic effect."

DUB cartoonist Niels Bongers depicted the minister in his strips quite often. "Her voluminous hair makes her instantly recognizable and she has a very expressive face, although I usually made her look serious or worried for comic effect."

The beginning

Two years earlier, in 2017, everything seemed to be just fine. In fact, political party D66 was celebrating. In the third cabinet led by Prime Minister Mark Rutte (comprising the parties VVD, CDA, D66 and ChristenUnie), D66 finally provided the Minister of Education, Culture and Science, something the centre-left party had never managed to do before, not even in the liberal and social democrat governments of the 1990s.

It was a long cherished dream. In its campaigns, D66 said it had great plans for education and research, so the expectations were high.

The party ended up choosing a senior figure for the role: Ingrid van Engelshoven. She had joined the party while she was still a university student working as a secretary to D66 founder Hans van Mierlo. When the party was virtually swept away in the parliamentary elections of 2006, retaining only three seats, Van Engelshoven became the party's chairperson and, together with the new leader Alexander Pechtold, put her shoulders to the wheel. “He did the campaigning, I looked after the in-house stuff, the organisation”, she declared in an interview with Dutch newspaper Trouw. Additionally, she had served as an alderman in The Hague for seven years, with a portfolio that included youth and education.

Admittedly, she has never had the gift of the gab. She hesitates mid-sentence and is not fond of one-liners. Furthermore, she had little experience with higher education and research upon taking office. On the other hand, she had a great deal of political and administrative experience.

Differences of opinion

In fact, the ministry was in need of a seasoned politician, because the coalition parties – VVD, CDA, D66 and ChristenUnie – had widely differing opinions on education and research. Take basic student grants, for instance. VVD and D66 abolished them in 2015, while CDA and ChristenUnie wanted to bring them back. The hard-won compromise in their coalition agreement was a discount on the tuition fees in the first year of studies (ultimately accepted, through gritted teeth, by the Senate) along with a rise in the interest rates on student loans (rejected by the Senate).

But there were many more sensitive topics in her portfolio, such as selective intake for study programmes, distribution of research funding, the binding study advice, and unequal opportunities. The minister had to navigate carefully – and with all her experience, she ought to have been well placed to succeed.

So how could it all go so horribly wrong that in September 2019 the Leiden vice-chancellor would receive her so icily and demonstrators would call on her to resign? It was all down to unfulfilled expectations. People expected more money and a progressive policy from a D66 minister, but there was little evidence of any of that.

Broken promise

The first blot on her copybook: the new government proposed an ‘efficiency cutback’ on education of 183 million euros, of which almost 44 million euros were to be taken away from higher education. Even young supporters of coalition parties VVD and D66 were angry. “Government breaks promise to students”, they wrote in a press release. After all, the basic student grant was abolished in order to invest more money into higher education, so they said. So how can you cream off money at the same time?

They should reduce the insane amount of meetings

Starting with a spending cut, as a minister of the pre-eminent party for education. It was not ideal, but her response to all the criticism did not really help either. The higher education institutions should reduce the huge number of meetings, was her suggestion. And – ironically enough – she planned to hold talks with the institutions about it.

Van Engelshoven visiting UU in March 2018. Photo: DUB

In addition, she put the blame on the previous government, which had apparently not estimated the number of university students and school pupils correctly. That was a weak argument, because ministers do not make such estimates themselves, and the decision to make cuts definitely came from the new government and therefore from the D66 minister.

The expression ‘efficiency cutback’ was, in any case, received badly. Work pressure and competition were already at intolerably high levels and education was being jeopardised, administrators and activists warned in unison. They demanded an extra billion euros. And it was Van Engelshoven’s thankless task to answer ‘no’.

Attempt number 1

So she was on a hiding to nothing. In September 2018, less than a year after taking office, she made an initial attempt to find a way out. Van Engelshoven decided to take the initiative.

With great conviction, she gave a speech at the opening of the academic year in Tilburg. Her message was that she would limit the binding study advice (BSA). Some students need time to get accustomed to higher education: one must not be sent away if they earn too few credits in their first year. The BSA standard should in any case not exceed 40 credits, the minister announced.

A robust policy, and it didn’t have to cost a single cent! At last, a discussion that was not about money but about progressive subjects like student well-being and equal opportunities. Van Engelshoven wanted to show decisiveness and dreamed of a victory for her party. Students would salute her for it; and the institutions… well, they would get used to it. Had there not long been a yearning for a less strict BSA in senior secondary vocational education?

But even the universities of applied sciences, generally less critical of the minister, felt aggrieved. Why had she not consulted them about it? And why was she even getting involved? The universities were more unhappy still.

She also came up against fierce opposition in the House of Representatives, including from coalition parties VVD and CDA. The coalition did not support her. She had to climb down and subsequently claimed that she had actually seen it coming. She just wanted to test the waters, she asserted.

Attempt number 2

Her opponents had the bit between their teeth. The universities gradually convinced everyone that they lacked funding. They demonstrated that they were getting less and less money per student (if you combine the budget for research and education).

Perception is everything, the minister must have been thinking. Or perhaps, attack is the best form of defence. In any event, that autumn of 2018 she made fun of their complaints about a lack of funding. They were fables, concocted at the ‘University of Hicktown’. In the House of Representatives she spoke scornfully about the logic of fairy tale character Holle Bolle Gijs, “who stuffed himself and was still so hungry that he couldn’t sleep”.

Holle Bolle Gijs, who stuffed himself and was so hungry that he couldn't sleep

“There are still people who want us to believe that all is doom and gloom in higher education, that we are on the brink of the precipice. If you don’t correct that perception, it will lead a life of its own”, she said.

She distributed a “straightforward list of figures” to make her point. But the opposition was easily able to counter her argument: she had not taken research funding into consideration. “You have a point there”, she admitted when someone mentioned the fact.

Natural Sciences

It did not enhance her reputation. And there was another thorny issue too. The government reassigned funds to natural sciences and technology. Many millions of euros were involved and the decision was taken rather abruptly. The ‘general’ universities in particular thought it was a ridiculous decision. Maybe natural sciences and technology did need more money, but why would you simply take it away from medical studies, humanities and social sciences?

A year later. It’s September 2, 2019, and Van Engelshoven has waved away the grumbling about the reassignment of funds. It had to be “quick and dirty”, she said in the newspaper NRC Handelsblad, because – by their own account – the technical and engineering programmes were unable to cope with the influx of students and were threatening to freeze admissions.

Quick and dirty: those words would continue to haunt her. “I’m not here to be liked”, she said in an interview that was published on the day she went to Leiden to make a speech and the vice-chancellor lashed out at her.

Let’s make it a billion

So relations were icy at the start of the academic year, in September 2019. Something had to change. Van Engelshoven needed to show that she was on the side of higher education and research.

Ingrid van Engelshoven presenting her Strategic Agenda in Utrecht. Photo: Marieke Duijsters

So three months later she began to adopt a different tone. She put forward her Strategic Agenda, writing in it: “No new government schemes for the time being.” She wanted to rein in the competitive drive, save small study programmes and keep universities of applied sciences in shrinking regions running.

All at once she proved the activists and lobbyists right: a lot more funding needed to go to higher education and research. She even gave a figure of a billion euros. She herself was bound by the coalition agreement, so it would have to be the task of the next government. The new tone helped a little, but her critics could take pot shots at her: if that was really her opinion, why didn’t she do anything?

Another comic strip by Niels Bongers, titled "investing in higher education". In it, Van Engelshoven laments: "It's impossible to do something so big in just four years."

Coronavirus, a gift fallen from the sky

And then came the coronavirus. Nobody wishes for a global pandemic, but from a political viewpoint the coronavirus crisis was manna from heaven for Van Engelshoven. As from the spring of 2020 she was at last able to do what she does well: holding discussions, making compromises and getting things done. One decision after another was taken in the light of the exceptional circumstances. She was finally able to make her mark. For example, the binding study advice was postponed or relaxed, given that all study programmes had to provide online education. Nobody screamed blue murder. Now there were no more obstacles.

Covid-19: she was finally able to make her mark

She then took some more robust decisions. Pupils in senior secondary vocational education would be allowed to go forward to higher professional education even if they had not yet got their diploma. Deferred final-year students got coronavirus support. And, to a certain extent, she stood up for young researchers. Were universities complaining that researchers couldn’t get their work finished within the time constraints of their temporary contract? Simply give them a permanent contract, was her answer, which she later qualified somewhat.

Criticism of her policy could still be heard – students felt they had been forgotten when all the billions in coronavirus support were distributed – but she shrugged it off. We were in a crisis, we had to carry on.

And in the coronavirus crisis the educational institutions would not have to stick to all the deadlines and quality agreements, she promised. They were already having a tough time, so they should be allowed to do their work without her getting in the way. Suddenly, the cooperation with the sector appeared to be smoother.

Additionally, at the start of the present academic year 2021-2022, Van Engelshoven put her colleagues in the caretaker government on the spot. Higher education would not shut up shop again, she promised, not even if there were to be a fourth wave of coronavirus. That would not be good for the students. The government speaks with one voice, so she made her promise on behalf of all the members.

At the end of November, Maurice Limmen of the Netherlands Association of Universities of Applied Sciences sung her praises. “I have taken part in a lot of administrative consultations, but if there is anyone in the past eighteen months who has advocated keeping education open and considering the wellbeing of students, it’s this minister.” They are doubtless both disappointed that there is now yet another lockdown.

Diversity

In 2020 she was finally able to show her credentials as a progressive minister. She promoted diversity and inclusion. She signed an action plan drawn up by universities and scientific organisations that wanted to combat discrimination and sexism within their own ranks. The aim was to create more opportunities for women in science, people with a migration background and other people that are hampered for one reason or another.

This worked like a red flag to a bull, especially on the right of the political spectrum. Perhaps universities ought to keep lists of scientists and their origins? Would diversity police be present on the campus? Don’t make things any crazier. Judge everyone simply on their qualities, said Dutch right-wingers. The majority of the House of Representatives agreed with that view: get rid of those plans.

Opposition to diversity policy: “I am still frequently surprised”

The minister was able to respond from the viewpoint of her ideology. “I am still frequently surprised by the opposition to promoting diversity in society”, she lamented in the House. “It’s a pity that people are not judged on their abilities. If they were, our universities would look much more diverse.”

Clever: she couldn’t actually lose those heated debates in the House of Representatives. Higher education institutions have complete freedom to conduct their own policy and they stand behind the plans. Van Engelshoven was happy to be the progressive fall-guy that shielded the universities, but actually she had little to do with it.

"Sorry, I'm in a caretaker capacity", says the minister in this strip by Niels Bongers.

Elections

When somebody asks her what her legacy is, Van Engelshoven always talks about the ‘efficient thinking’ that this government broke away from. Under her leadership the ministry made no firm numerical demands on higher education institutions. They could operate the ‘quality agreements’ that they had established with their participation councils. And during the crisis they could delay making those plans too.

And, as she herself is happy to point out, she asked consultants PwC to give an opinion on the funding of higher education. Is there still enough money? The answer was no. Van Engelshoven feels there is at last a solid foundation for the appeal for extra funding – and the next government can do something about it.

In the run-up to the elections, she suggested that the criticism of her policy ought really to be directed at the VVD. That was the party that put higher education cuts in the election plans. “Now maybe you understand what I have been up against in the last few years”, she said somewhat sadly but with a note of triumph.

“Now maybe you understand what I've been up against”

And maybe she has a point. In any event, students, researchers and teachers seemed to be somewhat less critical at the end of her term of office. They had revised their expectations and were looking ahead to the next government. Maybe it could do more for them, they thought.

New government

And now there is a new government, with the same coalition parties. Apparently, Van Engelshoven was not willing to return. Her successor: the well-known theoretical physicist Robbert Dijkgraaf.

The new coalition agreement includes extra investments in higher education and research. Furthermore, the line of more stable financing will definitely be continued, so Van Engelshoven’s legacy is assured. Let’s wait and see if Dijkgraaf can benefit from it.

Ingrid van Engelshoven (1966) went to high school in Belgium. She moved to the Netherlands to study Political Science at Radboud University Nijmegen and law at Leiden University. She's served as chair for political party D66 and alderman for Education in The Hague. Previous roles also include partner at a consultancy firm and director of the Dutch Foundation for Responsible Alcohol Consumption (STIVA), a partnership between the producers and importers of beer, wine and spirits. In October 2017, she became the Minister of Education, Culture and Science in the third Rutte cabinet.

HOP author: Bas Belleman