Global warming

UU student's mind filled with uncomfortable questions during North Pole expedition

"Why are you flying if you're a climate scientist?" I couldn't help but ask myself this confronting question when I stepped onto a plane to the North Pole in June to join the Science Expedition Edgeøya Svalbard (SEES), whose goal is to quantify the impact of global warming. I was the only student in the group. Eastern Svalbard has gone through one of the highest temperature increases on Earth because of climate change.

I’m writing a dissertation about Arctic lakes as part of the Masters' programme in Earth Sciences, with Wim Hoek as my supervisor. He also joined the SEES in 2015. This time, he needed help with drilling in lakes to reconstruct past climate fluctuations. As for me, I needed the samples for my Master's research. Apart from us, there were 49 other scientists from the Netherlands and abroad, as well as 36 tourists.

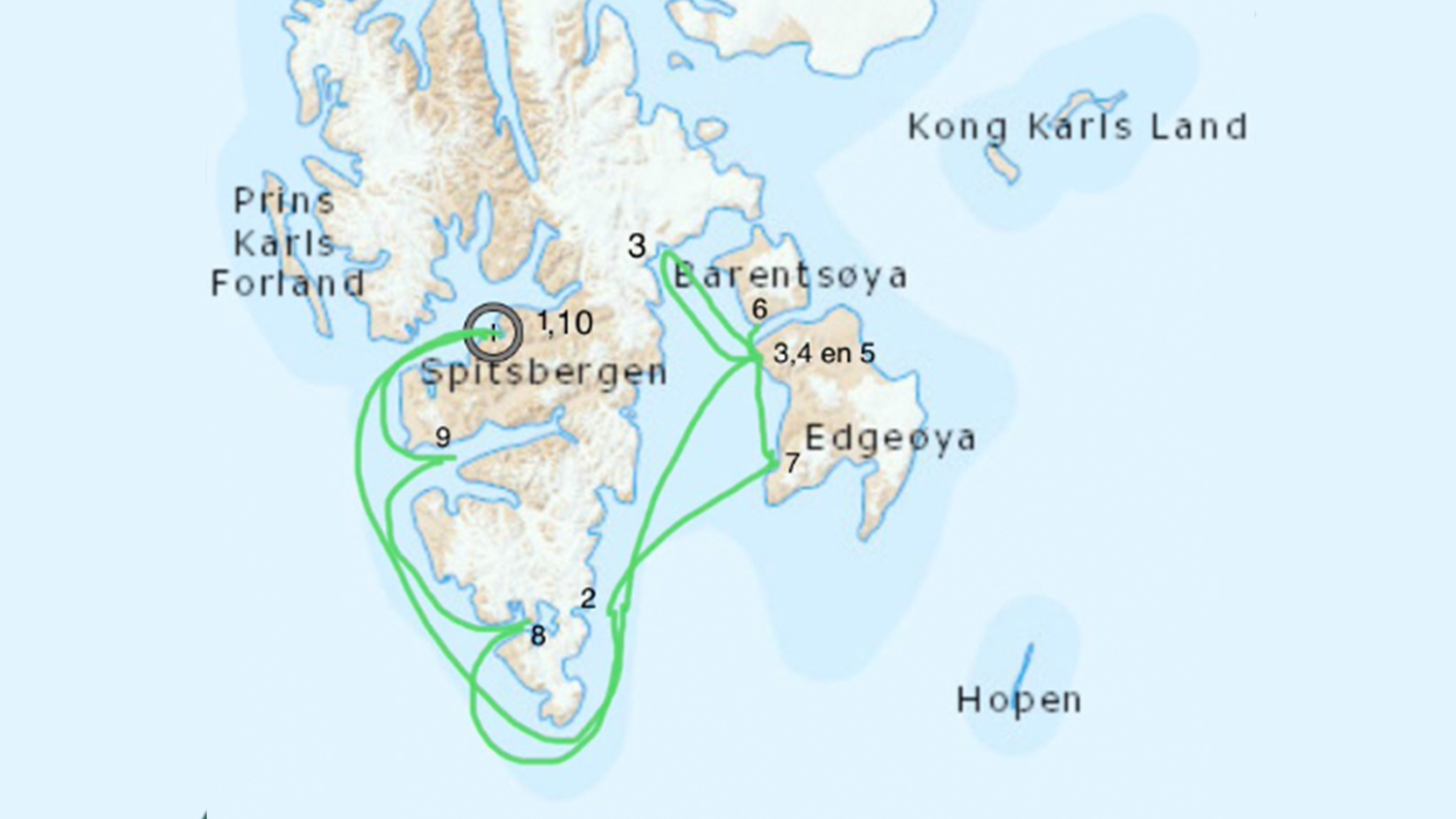

Route of the SEES expedition in 2022.

Route of the SEES expedition in 2022.

More than ever, I was conscious of how human activity has led to global warming. I also wondered to what extent we are willing to adjust our behaviour to prevent further warming. One day, a barbecue was organised on the ship where we were staying. I thought: "How seriously will people take our results if we are roasting meat for all these people on an energy-guzzling boat in a region where the consequences of climate change are extreme?"

You can hear the glacier melting

“Polar bear spotted on the coast!” The message was blasted through the speakers at 7:00 am. I was immediately wide awake and ran towards the deck. At the time, everybody was still excited about seeing polar bears in the wild. Unfortunately, the euphoria didn’t last long because the polar bears ended up hindering our research. We couldn’t reach the shore because of them.

After a few failed attempts to get to the land, I'd had enough of polar bears. “Another one?” When time became pressing, we eventually landed with two rubber boats on the south side of Barentsøya, even though three polar bears had been spotted in the area. We were heading for lake Andsjøen, where a drill core had been taken in 2015. My goal was to retrieve sediments (also known by their popular name, "mud") in order to collect information from 2015 until now. The samples are for my dissertation, which aims to provide better insight into climate changes over time. This information is stored in the different soil layers of the lake.

Collecting material from the drill core with Wim Hoek

Collecting material from the drill core with Wim Hoek

The effects of climate change were painfully visible in our many excursions. For example, we were able to sail with our rubber boats along a glacier. Now I understand where the inspiration for the “wall” on Game of Thrones comes from. A gigantic wall of ice is sliding into the water! It was really confronting to be able to observe just how much the Earth is warming up. We were sailing through water that was still frozen only a few years ago, not to mention we could literally see and hear the ice melting, feeling powerless. But then I asked myself whether we were genuinely powerless or rather misusing our power.

The "wall" from Game of Thrones in real life

Paradoxes

Throughout the 9-day expedition, I often wondered if I was even supposed to be there. I love standing out, being different. I want to visit unique places. Being a polar explorer fits the bill because not many people get the opportunity to make such a journey. But if so few people go there, should this expedition even be taking place at all?

I comforted myself with the thought that I have contributed something by being on a research vessel. But the tourists were doing the same thing. To make them feel more comfortable, the word "tourist" was taboo during the expedition — we said "science supporters" instead. Hopefully, the positive impact of this trip will outweigh its negative impact.

Anchor point for the Negribreen Glacier

Anchor point for the Negribreen Glacier

We weren’t allowed to set foot on land if we saw a polar bear because we would disturb its habitat. When you shoot a polar bear for self-defence, for example, the police conduct a CSI-like investigation to determine whether you really had a justifiable reason to kill the animal. So, why are we avoiding a single (!) polar bear, while in the Netherlands, so many animals are being slaughtered daily? Because the polar bear lives there, we are the uninvited visitors.

In Svalbard, nature comes first and we humans come second. Ideally, we should live in balance with nature. However, we are (unfortunately) too many, so we must place ourselves at the top to survive. My question is: if the polar bear belongs there, where do we belong? We have multiplied ourselves so much that we are increasingly expanding our habitat and reducing it for all other organisms. This is going so far that polar bears are visiting the inhabited world, while we are cramming livestock in a barn.

I have never completely been vegetarian or vegan because I always thought that livestock in the Netherlands is just the unlucky generation of the animal world, a role which we have bestowed upon them. But since I am also part of the so-called unlucky generation, I realised that what is happening is extremely unjust. In my opinion, tourists and scientists don’t belong in the polar bear's space. But I’m also convinced that livestock doesn’t belong in our space. Even if we had politely invited them, they would have declined our invitation.

Visiting a place where nature comes first puts yourself and humanity in a different perspective. The walls of ice, the steep mountains, and the green swampy glaciers were screaming at me: “You don’t belong here, leave it intact”. Yet, at the same time, I never felt closer to nature. That is one of the paradoxes that the North Pole brings about. At the beginning of our expedition, it was hard for me to accept that we, human beings, are not superior.

Children in the Netherlands are brought up with that idea: we are free, we can go wherever we want and say whatever we want. But now it's time to change our habits and let go of our liberties. Nature has been adapting to us for years. Now it is our turn to adapt to its needs. Fortunately, just like nature, we can change to delay the approaching doom we have created ourselves. Because one day, nature will certainly continue without us as a disturbing factor.

Swampy tundra

Swampy tundra

Lessons learned

The expedition was also marked by strong emotions such as fear, stress and anger about the choices and policies of others and shame about my own. Now I try to adjust my behaviour to minimise my impact on the climate. I became vegan, my wardrobe is 99 percent comprised of second-hand items and "not flying within Europe" was added to my perpetual to-do list.

However, as a scientist, you are required to provide objective information (another paradox). In the days before, during and after the SEES, there were multiple news articles about the expedition, all stressing the importance of climate engagement. Two of those articles, published by the Dutch newspapers Trouw and AD, had photos of Wim Hoek, Willem van der Bilt and myself. We also appeared a couple of times on the NOS eight o’clock news. I was even recognised by Dutch tourists when travelling back home. Through this publicity, I realised that research is not enough, it is also essential to share your story and try to move people and systems in the right direction, so we can balance living on earth and preserving it.

Being interviewed by the NOS (Photo by Rob Buiter)

Being interviewed by the NOS (Photo by Rob Buiter)

A huge thanks to all the people I met, spoke to, and shared this incredible experience with! Especially to Wim Hoek and Willem van der Bilt for letting me be part of the lake coring group. If you want to read more about my experiences (in English), please visit my blog.