The unlucky generation

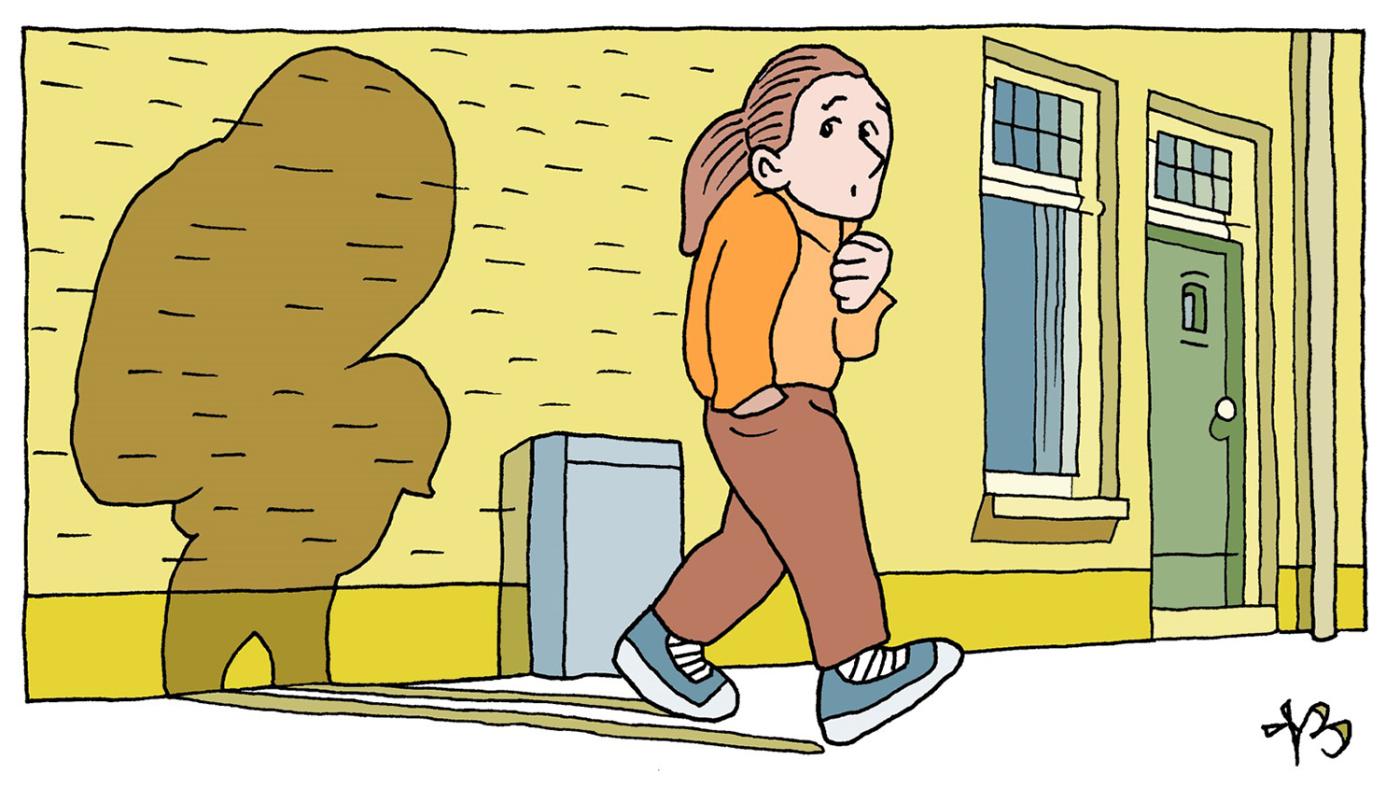

'It feels as though your college debt is constantly following you'

While the generations before them could count on benefits from the government, many of those who pursued an academic degree these past eight years had no choice but to take out a student loan. The Dutch government has since recognised that the loan system failed and decided to reintroduce the grant from September 2023 onwards.

The students of the unlucky generation fell between the cracks. That's painfully obvious when looking at Guusje, who’s doing a pre-Master’s in Psychology: “My older brother got a grant while he was in college. But I never got any, and neither will I be entitled to it once it returns because I’ve been studying for longer than four years.” She took out a loan with DUO so she could focus on her studies. Sometimes she worries about her debt, which currently amounts to 30,000 euros. “It’s not a great feeling to start off with that much debt. If I ever want to buy a house, it will be harder to get a mortgage.”

Structural problem

Those concerns are worsened by the overheated real estate market and the fact that students have to pay interest on their loans since January. Mervin, a Master’s student of Game & Media Technology, feels screwed: “We have to pay interest, but we thought we’d been promised an interest-free loan by the government. If a bank would do this, they would have countless lawsuits to respond to. But the government can just get away with it.”

Beau, a fifth-year History student, is just as outraged about the unforeseen interest. She reckons that her chances of ever buying a house are zero. Even so, she does not like the term "unlucky generation" because, in her view, it implies that "no one chose for things to go this way when, in fact, this is a structural, systematic problem. Choices were made, in terms of policy, that put students in this situation.” Meio, a Master’s student of Organisational Psychology, agrees: “The word illustrates the way we are being treated, as if no one was to blame for the fact that we had to take out loans for our studies.”

Discovering who you are

One's years in college should be about discovering who they are, which includes moving out of their parents' home and learning to stand on their own two feet. For the loan generation, having to support themselves came with bigger consequences than for those who got study financing from the government. Meio borrowed about 20,000 euros and also received a supplementary grant. Right when he moved into his new home, he lost his job in the hospitality industry because of Covid and was forced to borrow even more money for a while. “I didn’t want to spend my college years as a hermit. People can say I could have made different choices: I could skipped my holidays or moved back in with my parents. But I think that’s asking too much of students.”

Beau has borrowed approximately 35,000 euros from DUO so far. For a while, she wondered whether or not she should join the board of her study association, UHSK, because that would require her to take on a higher loan. In the end, she decided to go for it, and she hasn't regretted it since. At first, she presumed that working hard would do: “I worked at the association five days a week and then took a side job on the weekend to make some extra cash.” But that turned out to be unsustainable in the long run. “You have to take care of yourself, too. It’s okay to have a drink every now and then without feeling guilty.”

More pressure

Students from the "unlucky generation" feel more pressured, according to a study conducted in 2019 by the student organisation ISO. Meio says he stressed out a lot about his finances but he presumes he’ll be able to earn a good salary after he graduates, so he's trying not to worry too much about his debt. “That’s easier said than done, though.”

Beau can relate: “It feels like your debt is constantly following you everywhere.” In her view, it’s important that students realise they only have a share of the metaphorical blame to carry. She really thinks this is a systematic problem. “Sometimes, I’m embarrassed about my debt. I think: 'Was this really necessary?' But, in the end, it can’t be all my fault. There are so many people dealing with the same thing as I am.”

Are your parents wealthy?

In a loan system, having wealthy parents who can support you financially makes all the difference, which means the loan system, which was meant to make things fairer, actually increases inequality. Beau has always worked around 20 hours a week next to her studies. “This makes it feel even more unfair, compared to students whose parents can afford to pay for everything.”

Guusje: “I have housemates who can’t get any financial support from their parents, so they work around the clock to scrape the necessary funds together,” which can have consequences for their mental health. “One of my roommates wanted to go to a psychologist but she just kept postponing it because she had to work.”

Ilse, a Nursing student at the University of Applied Sciences, took a loan from DUO and also received a supplementary grant. She has around 26,000 euros of debt but, contrary to many other students, she’s not too worried about it: “I’m so lucky that my parents and my boyfriend aren’t broke, so they can help me, but the same can’t be said about most students.” Mervin, too, says he’s on a luxurious position. “My parents wanted to help me out by paying my rent. That means I can make ends meet without taking out a loan. I would never have been able to make it without my parents.”

Compensation

The Dutch government has earmarked one billion euros to compensate the students who missed out on the grant. That makes around 1,400 euros per student — not nearly enough, most students say. It’s understandable they think this way. After all, those starting their studies in September 2023 will receive a total of 15,166 euros of study financing over four years. The new generation of students will then get over ten times as much money from the government. Beau: “That compensation is pathetic, there’s no compassion or sense of responsibility on their part. You can’t even pay one year's worth of tuition fees with this money.” Guusje, too, thinks the proposal is nonsensical. “It’s like they're kicking us when we’re already down. Of course, you can sort of control how much loan you take out and it is impossible to waive everyone’s debts but the compensation should be much higher.”

Ilse agrees: “It was an experiment to see what abolishing study financing would be like, and that experiment has failed. Fair enough, but then at least give back the grant for all the months students have missed out on it.”

*Calculated for students not living with their parents and based on the purchasing power in 2023/2024, which means the student will get 164 additional euros per month that year.