Henk van Rinsum launches book on Utrecht University’s colonial history

‘Utrecht scientists were part of the colonial system too’

Should UU apologise for its own history of slavery? That question came up last year after research showed that the university had more to do with oppression and exploitation than it might have been assumed. Advised by a committee, the university administration announced that research would be carried out into what is described as “an underexposed facet” of the university’s past.

Henk van Rinsum knew right away that this research should not be limited to studying the professors who had economic ties to the plantations or the university buildings on Drift and Janskerkhof that were purchased with the proceeds from the plantations. To him, the university's role in colonial times and the development of science in Utrecht in those times were much more significant. His new book, Universiteit Utrecht en koloniale kennis (Utrecht University and Colonial Knowledge, Ed.) will be published next Monday.

The book outlines a connection that may also apply to the study of the Dutch slavery history, based on the experiences of various professors who had a leading role in the contacts with the colonies. Until the 20th century, Utrecht University was little more than a collection of individual professors. “This book is not directly about slavery, or about the history of slavery at UU, but it does show how Western superiority thinking has determined that university colonial past.”

Henk van Rinsum. Personal photo.

‘I'm being timely with this book’

Henk van Rinsum knows what he is talking about. As a historian and anthropologist, he worked for 25 years at UU in the field of international cooperation. In the 80s and 90s, there were often joint projects with universities in Asia, Latin America and Africa.

He started having "increasing doubts" during his many visits to foreign universities as part of university delegations. The modern Western way of doing research was more or less imposed as the norm. “We wanted to do the right thing, but the relationship with other universities was based on the idea that ‘we are developed, and they are not yet’.”

In 2001, he wrote a dissertation in which he criticised the dominance of that concept of "development" based on his experiences with a collaborative project between the Utrecht Faculty of Theology and the University of Zimbabwe. He then continued his research, with a special focus on the relationship between the university and the colonial world. In 2006, he published a book about the history of Utrecht’s ties with South Africa.

Now he is publishing a new book, focusing on the contacts with the former Dutch East Indies. What is now Indonesia officially became a Dutch colony in 1816, but the archipelago had already been "conquered" by the Dutch since the end of the 16th century. More and more UU graduates and scientists started moving there.

“I have been researching this topic for at least 20 years. Suddenly, people seem to be paying more attention to these unequal relationships. I’ve been kind of embraced by time, so I’m being timely with this book.”

'That's when things go wrong: black people at the bottom and white people on top'

According to his book, until the middle of the 19th century, preachers educated in Utrecht were the ones who went to the colonies most often. Following its foundation in 1636, the Faculty of Theology, with Gisbertus Voetius as its eminent leader, remained the most important faculty within the university for a long time.

UU graduates followed in the footsteps of the merchant ships of the Dutch East India Company and the West India Company at all kinds of outposts around the world.

Henk van Rinsum considers them the pioneers of a centuries-long intellectual "civilising mission". Alumnus Johan Basseliers, for example, had set himself the goal of "bathing not only our Christian youth but also those foreign and indigenous dark-skinned people in the sun of our justice".

From 1850 onwards, a real research culture emerged at the university for the first time, thanks to the Enlightenment. Paradoxically, the strong emphasis on reason rather than religion did not lead to a different approach regarding the colonies, on the contrary.

Feelings of superiority and the idea that Western people were more developed often came to the fore even more vividly. “There was a great need to classify the environment. Plants, trees, animals and also people. That’s where things went wrong: black people were put at the bottom of the list, and white people at the top.”

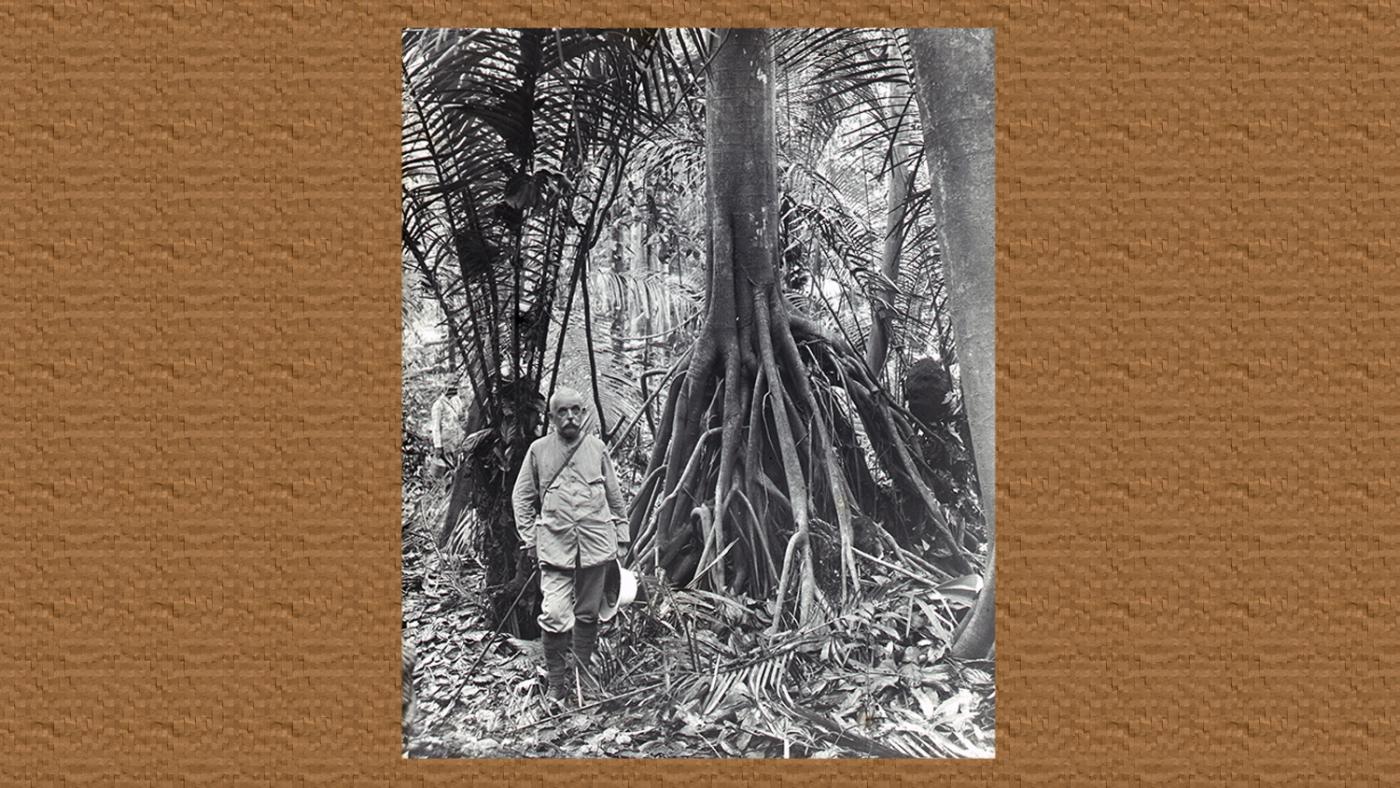

Friedrich Went didn't only go to the Indies but to Suriname as well. Photo: University Museum

‘Went motivated students to go to the Indies’

The natural sciences underwent a spectacular development during that period. The interaction with the colonial presence is undeniable. Van Rinsum emphasises the significance of professors Gerrit Jan Mulder and Friedrich Went, who specialised in Chemistry and Biology, respectively.

Mulder (1802 – 1880) was the founder of laboratory education in Utrecht. Dozens of military pharmacists were educated in Utrecht. Other students brought their knowledge to the Indies and thus promoted the exploitation of all kinds of minerals.

Together with his colleague Friedrich Miquel, Mulder advised on the introduction of Cinchona culture in the Indies. Quinine, extracted from the bark of the Cinchona plant, was an effective antimalarial agent. At the end of the 19th century, 90 percent of the global quinine production came from the Dutch East Indies.

But Henk van Rinsum says that Friedrich Went (1863 – 1935), after whom a cube-shaped building in the science park was named (it has since been demolished to make room for the new RIVM building) was really "a pure-blooded colonial".

“I don't mean it in a negative way. Went was a scientist who was actually rooted in the Indies. He worked there at the sugar and coffee testing stations. After returning to the Netherlands, he improved the botanical lab facilities on Lange Nieuwstraat and the number of students increased sharply. Went motivated those students to go to the Indies. He invariably insisted that the colonies were incredibly important for the development of science.”

‘Scientists were part of colonial rule’

Professor Went was an exponent of the "Ethical Policies" that the Dutch colonial government introduced at the beginning of the 20th century, according to which the Indies could no longer be seen as a mere "conquered land". The population and the country had to be developed, so that the Dutch could withdraw one day with peace of mind.

Im his view, scientific research was also part of that civilisational operation. “Thanks to people like him, science was indeed brought to the colonies but not necessarily to the people there, unfortunately. It was mainly the Dutch business community that was able to make use of it.”

Henk van Rinsum points out that it was precisely during the Ethical Policies period that the exploitation of raw materials in the outlying regions increased, partly out of fear of the British, who were trying to take over the trade.

He concludes: “The development of science at UU benefited from the colonies, certainly in Chemistry and Biology, but also in Geology. Yes, you could say that it was at the expense of the population there. The scientists were part of colonial rule. They were not the exploiters themselves, but they were part of the structure that maintained the exploitation. It was the merchant and the vicar, and the scientist joined in.”

But he insists that he doesn’t want to pass judgment. “I wonder what I would have done as a professor at that time. Not much else, I’m afraid. That’s just the way things worked at the time.”

‘It was like swearing in the entrepreneurial church’

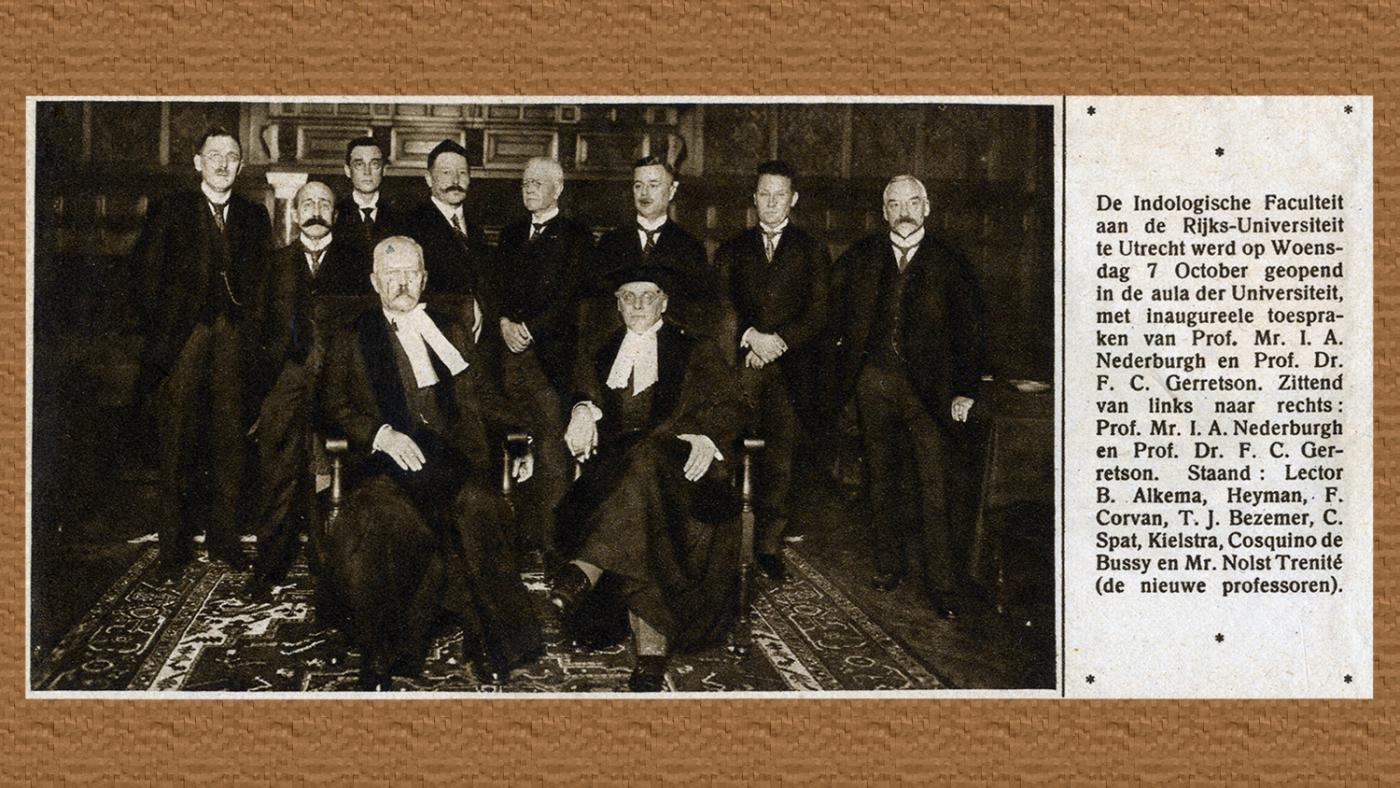

Nevertheless, he wants to regard the so-called "oil faculty" as a “stain on UU’s history”. The oil faculty, or sugar faculty, was the "derogatory" name for a new faculty of Indological Studies for colonial officials, which was inaugurated in Utrecht in 1925. The faculty was funded by the Batavian Petroleum Company and the sugar companies, among others. “That training program was aimed at conveying an ideology and to maintain the colony.”

The initiative was a response to the major concerns about the programme for civil servants in Leiden. In the opinion of many industrialists, it had become too libertine. “There was even talk of Indonesia as if it were a unitary state. That was like swearing in the entrepreneurial church.”

According to him, the fact that the program found shelter in Utrecht, after some peddling, has to do with the strong conservative-liberal and Christian-historical thinking at the university at the time. “To put it bluntly, the thought was: that which is given by God is good. If colonial relations are God-given, you have to preserve them.”

It is illustrative that the UU legal scholar Nederburgh defended the concept of "copyright". This right assumed, among other things, that someone who had developed a country should have more say over it than someone who was born there.

Stories about other professors also raise eyebrows. Carel Gerretson, the founder of the oil faculty, was certainly not the only scholar with right-wing sympathies. This professor of Japanese studies maintained friendly ties with Mussolini and even his letters with Fascismo è salvezza (‘Fascism is Salvation,' Ed.). “But, in the end, the study materials were not that different from the ones used in Leiden. Students even read books by Leiden professors.”

A portrait of professors at the inauguration of the Indological Faculty. Photo: Utrecht Archives

‘It's about a sense of displacement’

Henk van Rinsum says that he did not want to write about "the big, all-encompassing story" of the university’s colonial role. “I call it an exploration. Much more has been written on this topic than you might think, which is why I have included an extensive bibliography. But there is still a lot of room for additional research, obviously. I am very pleased that someone at the Faculty of Geosciences is now doing a PhD on the colonial background of the development of geosciences.”

Whether his book and the other research projects currently underway should ultimately lead to an apology from the university, perhaps even for its entire colonial past, is a difficult question for him. “I wonder if anyone wants an apology from a university. And who should they apologise to?”

In his view, other things are more relevant. “I think it’s much more important that we learn from the past, think about what kind of university we want to be, and what actions are in accordance with that.”

He is annoyed at what he sees as the narrow mentality about higher education that is now rampant in The Hague. According to him, a university's "true soul" is “cosmopolitan”. Van Rinsum: “I’m not talking about scientists happily flying around the world from conference to conference. But rather about a sense of ‘displacement’, the realisation that there are many more perspectives than the view you were taught at home.”

‘It would be interesting to have someone from a former colony take a look at UU's colonial past'

Therefore, he advocates re-strengthening ties with universities in Asia, Latin America and Africa. “A fund for joint PhDs and joint research programmes would be a good idea. That’s where I think we need to go: real cooperation without the concept of ‘development.’”

According to Van Rinsum, UU has a lot to gain by being truly open to other perspectives. “We are now making all kinds of laudable attempts to decolonise our curriculum, but perhaps we should ask someone from Indonesia to take a look at it.”

“I’m not exempt either. The justified criticism people can have about my book, though I can’t help it, is that I’m a white man with the perspective of a white man. The protagonists in my book are also all white and almost exclusively men. I would find it very interesting to give someone from a former colony the opportunity to look at UU's colonial past. How do they see it? I’m really curious to see what that would yield.”

On Monday, October 30, Henk van Rinsum will launch his book at the Utrecht University Building. After an interview with the author, there will be a panel discussion about the significance of UU’s colonial past. To attend the event, which will be in Dutch, you should register through this link.

The book ‘Universiteit Utrecht en koloniale kennis; Bestuderen, bemeten en beleren sinds 1636’ is available for purchase on the website of its publisher, Walburg Pers.

DUB may give away three copies to readers of our website. Interested? Email: dubredactie@uu.nl.