UU to have more evening classes due to explosive growth in the number of students

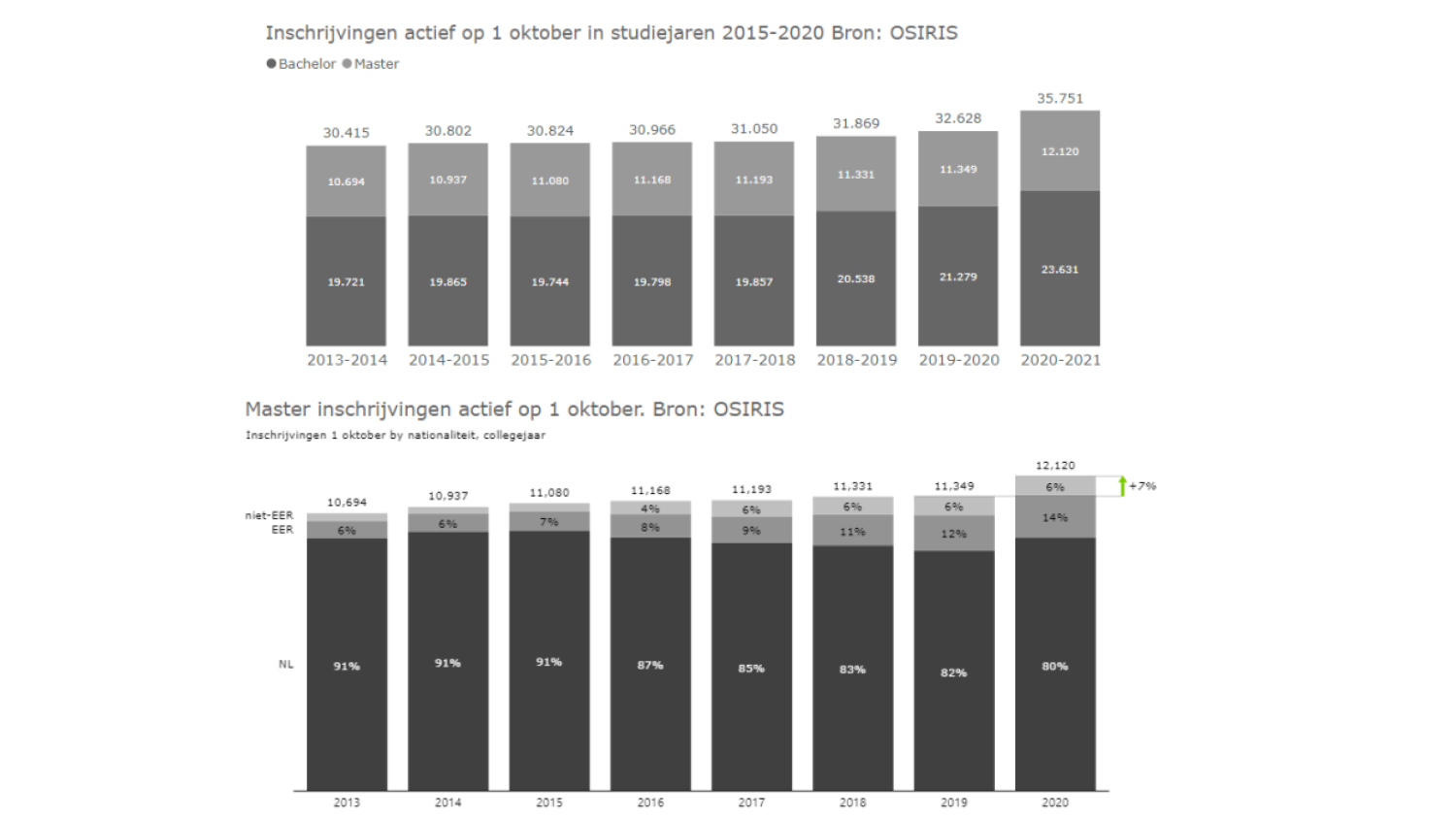

Up until two years ago, the number of UU students was growing by a few percentage points each year, but the Covid crisis has led to an explosion: last academic year, registrations increased almost 15 percent to around 39.000 students. This year, 5,000 more students enrolled in our university than in 2019-2020.

The Dutch Ministry of Education estimates that the number of university students is going to keep on rising until at least 2030. The number of enrollments is expected to increase by a further 15 percent in the next six years. International students, who have been coming to Utrecht in ever increasing numbers, play a significant part in this phenomenon.

No balance

The effects of this steep growth are already noticeable at the university and student life in the city, the four members of the Executive Board told DUB. Not only are new students having to deal with the restrictions brought about by the coronavirus, but they are also encountering other types of obstacles, such as not being able to join a student or sports association because they have reached their maximum capacity. Finding a place to live, which has always been tricky in Utrecht, has now gotten even more difficult, as has securing spaces at the university for educational activities.

UU President Anton Pijpers says the substantial amount of students will inconvenience several things. There are too few options for housing, the teachers’ workload is too high and students do not always receive the attention they deserve. Pijpers thinks they could find a solution if the budget UU receives from the government would be sufficient. The universities have complained for years about the decreasing funding per student. “Several studies have confirmed that our claim of needing an additional 1.1 billion Euros is justified, and since that estimation the student body has grown even more. We’re very off balance.”

UU President Anton Pijpers says the substantial amount of students is going to be an incovenience in several aspects. In addition to the pressure on the housing market, teachers’ workload is going to get way too high and students will not always receive the attention they deserve. Pijpers thinks the university could find a solution if it got enough funds from the government. Dutch universities have been complaning about chronic underfunding for years. The amount of money available to invest in each student is only getting smaller and smaller. “Several study programmes confirm that our claim for an additional 1.1 billion euros is justified. Since that estimate, the student body has grown even more. We’re very off balance.”

UU President Anton Pijpers says the substantial amount of students is going to be an incovenience in several aspects. In addition to the pressure on the housing market, teachers’ workload is going to get way too high and students will not always receive the attention they deserve. Pijpers thinks the university could find a solution if it got enough funds from the government. Dutch universities have been complaning about chronic underfunding for years. The amount of money available to invest in each student is only getting smaller and smaller. “Several study programmes confirm that our claim for an additional 1.1 billion euros is justified. Since that estimate, the student body has grown even more. We’re very off balance.”

But this budget increase is nowhere in sight. First, a new cabinet must be formed -- and it's not certain whether the new coalition government is going to increase the budget for higher education after all. But Utrecht University decided to take action right away, by freeing 50 million euros to hire more teachers and convert the contracts of current teachers from temporary to permanent. These measures aim to aleviate the worload and pressure teachers face right now.

The board members are not planning on allocating more money to build or buy new buildings, however. That's because significant investments in educational facilities (most of them in the city centre) have already been planned. “It’s so easy to say 'more students, more space'”, says Vice-president Margot van der Starre. “But all the money that goes toward housing cannot go toward education and research. That’s why UU is committed to spending no more than 15 percent of its academic budget on housing.”

The board members are not planning on allocating more money to build or buy new buildings, however. That's because significant investments in educational facilities (most of them in the city centre) have already been planned. “It’s so easy to say 'more students, more space'”, says Vice-president Margot van der Starre. “But all the money that goes toward housing cannot go toward education and research. That’s why UU is committed to spending no more than 15 percent of its academic budget on housing.”

We need to use our buildings more efficiently

To alleviate the most pressing issues, the university is going to rent additional space soon, reveals the vice-president. Last week, UU annouced that lectures and work groups are going to be held in a building on Daltonlaan Avenue from January onwards. “But, in the long run, our main goal is to use the buildings we already own more efficiently.”

In addition, Van der Starre expects UU employees to work from home more often in the future, which is going to lessen the need for office space, liberating rooms for teaching. She thinks that scheduling could be more efficient, too: for starters, she would like to prevent spaces from being vacant during the day and make more use of the evening hours. “We will do this in coordination with everyone involved, and it's certainly not going to happen right now. Everyone is very busy now because of the Covid crisis, so that would be impossible.”

Meanwhile, the Executive Board is already looking ahead to the next academic year, says rector Henk Kummeling. According to him, it’s inevitable for UU to schedule more lectures in the evening hours. At first, this will mean the time slot between 5:00 pm and 7:00 pm, but it's possible that some lectures will be scheduled at times that have only incidentally been occupied by exams up until now, namely between 7:00 pm and 9:00 pm and between 8:00 pm and 10:00 pm. “Absolutely not every teacher, every night. We’re thinking of one course a year per teacher, and then only one evening.”

Over the next few months, the rector is planning to talk about this with students and employees. The University Council is going to be involved as well.

Online education is not second best

In the rector's view, the university should take advantage of the lessons it's learned in the pandemic, one of them being that online education does not have to be inferior to face-to-face education. “We need to think more thoroughly about which forms of education should take place in person, which ones should take place online, and which ones deserve a blended version of the two. When do we need to gather on campus, and when can we go without it?”

He guarantees that this will not compromise the quality of education. “We advocate for Utrecht’s education model, which is small-scale and energizing, with enough contact hours.” However, the definition of ‘contact hour’ may be adjusted. Kummeling has been discussing this topic with the University Council lately. “I think a contact hour doesn’t necessarily mean gathering everyone in a space. There are meaningful, energizing ways of teaching that can take place online, it’s not second best.”

One evening class a week is negotiable

That doesn't sound like a nice message for students and lecturers: more classes in the evening and less classes in person. Pijpers: “This is mainly about a targeted approach and clear communication. For example, some teachers have told me that they have small children so we can't count on them between 5:00 pm and 8:00 pm. But if there’s one course a year in which I have to teach between 8:00 pm and 10:00 pm once a week, and I know about it long in advance, then that’s negotiable. And of course that means they are able to take time off at another time.”

Doesn't the board think the students will stay away from the evening classes? Time will tell, answer the three members. Kummeling: “The choice is simple, really. We can either build more buildings and provide lower quality education, of try to decrease costs for extra education facilities and keep up the quality. We don’t see a lot more options.”

Merel Dekker, Student Advisor to the Executive Board, is following the discussion with a critical eye. She thinks it’s crucial that students be involved in these plans in a timely and thorough manner. She agrees that one course comprising evening lectures once week is going to be regarded as acceptable by many students. “But, as I’ve also said in the board meeting, we need to remember that students often dedicate their evenings to activities organised by student associations, and many of them have jobs. So evening classes need to be limited, and students must be informed in time so that they can adjust their schedule.”

The space we have should be used differently

Dekker also thinks that the demand for student housing is so high in some places because there are fewer places students can meet for student association activities. “Attending university is more than going to lectures, you also want to develop socially,” she says.

According to Kummeling, UU is striving to spare student associations as much as possible in its plans to make a more efficient use of its buildings. Recently, the university decided to set up a temporary living room for students where student pavilion De Vagant used to be four years ago.

The rector thinks the efforts towards housing efficiency the UU can go together with community building, which the board also acknowledges is of great importance. “Most of all, we need to use the space we have differently. For employees, this will mean that focused work is going to be done at home, while the office will be a space for meetings. For students, this means that a part of instruction-based education will occur at home, while the campus will be a place to get together and debate.”

It's about stabilising

But is the Executive Board powerless in reducing the influx of new students? According to Anton Pijpers, UU has lacked a growth strategy for years, consciously choosing not to perform unbridled student recruitment. “That went well between 2012 and 2019. We did grow, thanks to the quality of our education and research, as well as the popularity of Utrecht as a city, but we grew a lot less than other Dutch universities. It wasn't an issue to us that that meant surrendering some of our market value. The past two years have really been marked by astounding growth, which means we need to take action.”

According to rector Kummeling, a uniform approach to slow down the growth of UU's student body across all degrees isn’t imminent. “We can’t escape a targeted approach. Some studies actually want to get more students, whereas some would prefer to have fewer. We can adjust information provision, matching and selection accordingly.” Sometimes, a university simply has to limit the influx of students, ponders the rector. “The laboratory spaces at the Faculty of Science and Geosciences, for instance, only have so much space.”

Kummeling adds that slowing down the growth of UU's Bachelor’s programems is hard as, in principle, they are obliges to admit all students. “But we want to examine, together with other universities, if we can set a fixed amount of students for some programmes. Most of all, it’s about stabilisation and maintaining the quality of our education.”

Don't come to Utrecht if you don't have a room

Apart from the increased influx of Dutch students, the amount of international students has risen, too. Right now, 13 percent of UU students come from abroad. In other Dutch universities, that proportion is twice as high on average. The number of international students in the Netherlands is expected to grow around 40 percent in the next six years. UU can therefore expect the amount of internationals to keep on growing.

That is worrisome for the housing market, which is already highly competitive. To Van der Starre, the housing problems are “incredibly poignant”. She says the university tries to warn every international student about the situation, supporting them in the best way it can. In addition, UU has been making efforts to increase the number of rooms available for international students, but it can only do so much, so change is taking place slowly. The vice-president thinks that, next summer, UU will literally be telling international students not to come to UTrecht if they don't have a room lined up. “But some will come even then.”

According to the rector, the academic world is international by default, and studying abroad is part of that. UU agrees that it is of the utmost importance. But Kummeling thinks things have come to such a point that they require a critical assessment: in which programmes does UU need more international students, and in which ones they do not? “For which educational programme do we really need an international classroom, and for which ones we don't? And what should such a classroom look like? You do not want all international students to come from the same country.”

The university prefers Master’s programmes to be more international than Bachelor’s programmes. The influx of the former can be controlled quite well through targeted information provision and a thorough selection. University boards, meanwhile, can define for themselves how many students are admitted to a Master’s program. In the Bachelor’s phase, there are fewer possibilities. All European students must be admitted either way.

Still, the Executive Board sees possibilities to regulate things for this group too, which is why it is keeping an eye on the formation of the new government. In the future, there might be an option for study programmes with both Dutch-language and English-language tracks, so that a fixed amount og students can be applied to the latter only. That plan is still awaiting the consideration of the Dutch senate. A different instrument the government could use is establishing a limit to the number of students originating from countries outside the European Economic Area, which could be achieved through migration laws.

Apart from that, the university can use its language policy. At the moment, a commission is working on sharpening UU's language policy in advance of a national law that is also awaiting approval by the Dutch senate. Under political pressure, the government is looking to be more strict when supervising the language of instruction used by study programmes in higher education. “Not every study needs to be taught in English”, states Kummeling. UU’s current policy is that most Master’s programmes are ministered in English, while the majority of Bachelor’s degrees are taught in Dutch. “We could be stricter with that.”

The board prefers not to say what kind of consequences that would have for existing programmes. “We will examine that in the coming months.”