UU rector’s vision for the future

Universities must open their doors to society

What is it about Utrecht rectors predicting the future of universities during their tenure? Bert van der Zwaan, Henk Kummeling’s predecessor, wrote a book titled Haalt de Universiteit 2040 in 2016 (Achieve the University from 2040 in 2016, Ed.) in which he advocated for a strong community, a great relationship between education and research, and good facilities. Otherwise, he feared that education at the university level would become fragmented, with students who would scrape a degree together by taking a number of digital courses.

Now it is the turn of the current rector, Henk Kummeling, to present his vision of the future. In his case, he’s looking at 2030. He wrote the book alongside Manon Kluijtmans and Frank Miedema. As director of the Centre for Academic Teaching (CAT), Kluijtmans specialises in education. Miedema, a former dean of the Faculty of Medicine, caused a furore thanks to the Science in Transition movement, in which he argued that scientific research should focus much more on social issues. Until recently, he served as dean of Open Science. The three authors held several meetings in which they asked students and staff to brainstorm together.

The result is the e-book The University in Transition (available only in Dutch, Ed.). It is exclusively available online and the authors also explicitly ask readers to leave comments, so that they can incorporate the input into a subsequent version of the book. Although the book claims to focus on universities in general, most of the examples and themes come from Utrecht.

Science in Transition. Photo: DUB

The authors Frank Miedema, Manon Kluijtmans and Henk Kummeling. Screenshot from a video by UU

The starting point of the book is here and now. The authors acknowledge that universities do not have it easy right now. For example, academic freedom is under pressure, there is scepticism in society about scientific research, and the pressure to perform among students and staff leads to questions such as "What type of achievements are actually worthwhile?"

In the authors' view, the solution is for universities to open their doors to society not only by making research results publicly accessible but also by collaborating much more often and more directly with society. This applies to both research and education. Such a starting point has consequences for universities' current design. How do the authors see this happening in practice? DUB picked out four themes from the book to discuss with them.

Mixed Classroom, Teaching and Learning Lab 2019. Photo: Hilde Segond von Banchet

Students must learn to look at themselves differently at university

Many students come to university to get a diploma and start working. But, according to the authors, that is not enough. Higher education should help shape the students as well. “University has a lasting impact on the rest of a student's life and therefore on the impact that this person will make on society.” The main idea is that a university education teaches us to look at the world around us differently. In their view, education is more than the neutral transfer of knowledge and teachers need to be aware of that. For instance, they mention community-engaged learning, in which education is directly connected to society. This can be done through social internships or projects in a certain neighbourhood. The Mixed Classroom project by the Urban Future Studio, in which students work together with policy staff to find solutions to societal problems, is a great example.

“We want to prepare our students to contribute to society, the environment, health and wellbeing, as well as to ecological, economic and social sustainability,” the chapter on education states. During their time at university, students must learn to think critically and collaborate with students from other disciplines and with the rest of society.

In their vision of the future, university students will be given an important role in the educational process. They will determine the study trajectory themselves, in consultation with the teacher, who will map out the curriculum. Taking the initiative will be appreciated, and making mistakes will not be punished thanks to an openness to risky projects. This will give the new generation of students a greater role to play in the design and implementation of their education.

A logical consequence of this is that testing will radically change. Wave goodbye to exams with multiple choice questions, and say hello to self-reflection on one’s own functioning. The authors observe that many innovations fail because the assessment remains the same. Tests should be about the student and the results should give the teacher insight into their progress. The teacher must give the student tools on how to develop further, something that the authors call the feed-up and feed-forward principle. Preferably, the learning activity should be the test at the same time. That's a proposition similar to programmatically testing, which they are already doing in the Master’s programme in Veterinary Medicine, where students create a portfolio for which they collect data points. Data points are all evaluations of their activities, such as the assessment of practical assignments, tests and 360-degree evaluations.

Charm EU, the Master's in Global Challenges for Sustainability. Photo: Nina van der Bent

Internationalisation and diversity are not a luxury but a necessity

We should first understand others and only then be understood. That is the slogan of the University Medical Centre Utrecht, which indicates how we should interact with each other. This view is endorsed by the authors, who consider genuine curiosity and interest in the other person as essential. They write that the pursuit of diversity and inclusion does not stem from an ideology but rather from an understanding of its importance.

They argue that, in society, we are constantly dealing with people who have different cultural backgrounds, not to mention that the labour market and academia are internationally oriented. “International cooperation is an absolute must for high-quality research and education.” Hence their opinion that there should be a mixed classroom where people from different nationalities discuss subjects with each other. They also praise the CharmEU Master’s programme, in which a group of students from different countries and Bachelor’s programmes work together on a common assignment.

The authors regret that many internationals do not feel at home at university. “The success of internationalisation should not be measured by intake figures but by how comfortable international students feel and how significant their unique contribution is. Students and staff with different cultural backgrounds and first-generation students do not have it easy either. At university, they have to deal with a so-called hidden culture: unwritten rules of the dominant social group that are alien to newcomers or can even lead to negative effects and prejudices. These students can hardly recognise themselves in the offered subject matter because of a hidden curriculum, which means that the emphasis is strongly put on the Western, white world and not on knowledge from other backgrounds. According to the authors, more attention could enrich cooperation and culture.

The university of the future must provide more diversity and ensure that people can work well together. The authors think that working in teams could help with this, so they advocate for a home base for everyone, an academic family, where students are really connected, where they can tell their stories and are missed by others when they are not there. For students, the tutor group might constitute the academic family. Employees are often part of specific teams, but with one home base, they have more support. When it comes to people who are new to the community, universities should make sure they get a buddy who helps them get acquainted with everything.

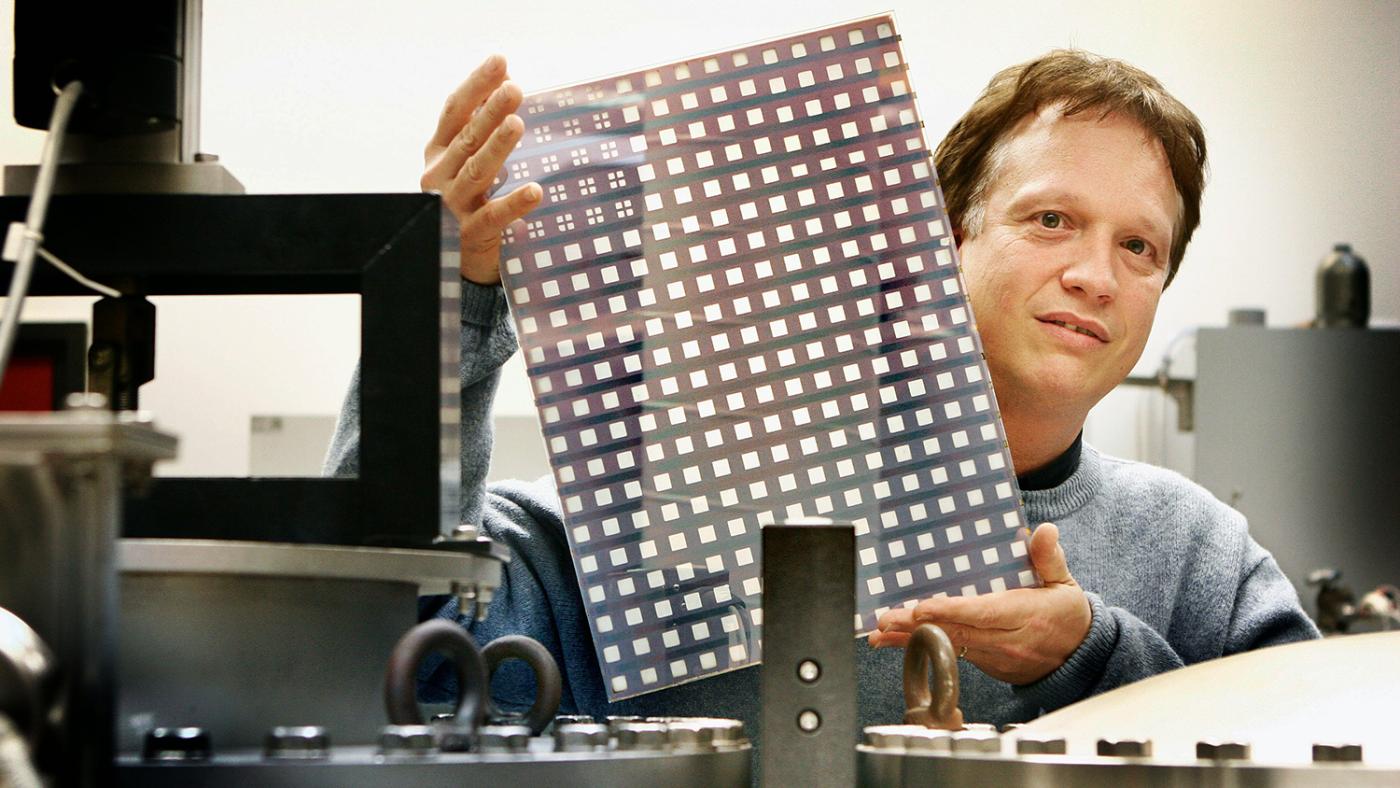

A young Rudolf Schropp with his solar panels. Photo: DUB

Sustainability day at UU, 2019. Photo: Robert Oosterbroek

The ‘neutral’ scientist must show how they want to improve the world

The authors poignantly outline the problem of how difficult it is for a scientist to present knowledge in a ‘neutral’ way. They usually disregard their own political preference, basing themselves only on scientific research. But how easy is that? “We know all too well how indirectly and often unconsciously, our personal preferences, experiences and opinions can play a role in our work.” But those who explicitly operate from a political preference are often not taken seriously. As a scientist, you will then have to show that all relevant scientific knowledge has been included in the judgment. You can see that in the climate crisis, for example.

The question that arises is whether scientists can make a constructive contribution to society and be sufficiently neutral. The authors say this depends on the context. When it comes to the fundamentals of our democracy, that’s not a problem. It becomes more difficult when it comes to a vision of the future or the pursuit of a new society. Then the consensus is less strong.

The starting point of the scientist should be: For which problem in society do I want to offer a solution and with whom am I going to work for this? However, the authors note that there is also a certain resistance when it comes to cooperation. They see that if one opens the door to public parties, this mainly benefits the big companies due to the rise of neoliberalism.

That changed after the financial crisis. The voice of the ordinary citizen is becoming bigger and more influential. However, one must prevent that knowledge from remaining unfairly distributed. In the development of a Covid vaccine, scientists collaborated well, but it proved difficult for poor, developing countries to obtain the vaccine.

The authors think that embracing the Sustainable Development Goals is the solution. These goals, they say, offer the appropriate tools to focus research on improving society, both for science and for alpha and gamma research. In addition, Open Science and Open Education must ensure that the solutions that scientists find and the education to disseminate that knowledge are not only limited to the Western world but also become available to the Global South.

Henk Kummeling signing the contract for Recognition & Rewards. Photo: UU

Give professionals more space and freedom

A recurring theme in the book is the damage that neoliberal politics has done since the 80s. Policies were focused on returns and efficiency. There was a strong sense of accountability with the result that universities had to hire more and more people to produce accountability figures. As a result, fewer people could be used for education and research.

In addition, the government only wanted to finance students who completed their studies within the set period. In order to achieve this, measures had to be taken that had to be checked. In research, grant money partly went to scientific organisations such as research funder NOW, which assessed individual applications. This created a competitive atmosphere in which the choice often fell on people who had published a lot. Whoever won a prize had a good chance of winning again in the next round.

The universities need to break free from this. The emphasis should be on teamwork and not on individual performance. Utrecht is trying to achieve this with the Recognition and Reward project. At the same time, teams should be given more of their own budget to give professionals more room to make their own decisions. They are then better placed to determine the content of the research and education themselves. Employee participation does not need to be overhauled, but it does need improvement, such as tenure tracks that are too short. This could be supplemented by what the authors call deliberative democracy, or groups of students and employees from the community who brainstorm about certain themes together.

For those who can read in Dutch, the book is available for download on UU's website, where you can also watch an interview with the book's authors.